THE LIFE OF THE arctic penguin has been well represented in films and documentaries in recent years as 4-foot tall emperor penguins have marched across our movie screens. Now new research shows that the ancestors of these modern-day giants, were larger, sturdier and lived in the deserts of Peru during one of the warmest periods on Earth—some 36 to 42 million years ago. A team of scientists from the U.S., Peru, and Argentina has found two new species of penguins that are challenging accepted theories of penguin evolution and migration.

Peruvian paleontologist Mario Urbina-Schmitt of the Museo de Historia Natural de San Marcos in Lima, who has logged more than 20 years of fieldwork in Peru, helped to locate the fossils. Unexplored areas can lead to exciting discoveries like the new species of giant penguin named Icadyptes salasi, the third largest penguin known to science. With a beak that measures more than two times the length of its skull, Icadyptes had the longest beak of any penguin in the world. A true giant, this magnificent bird stood about 5 feet tall, was sturdy in constitution and waddled about the deserts of Peru about 36 million years ago. The researchers also found a second, much older fossil from a 42-million-year-old deposit. The earlier penguin, Perudyptes devriesi, was three feet tall, which is comparable in size to today’s second largest living penguin, the King Penguin.

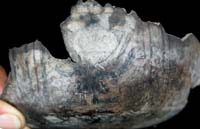

Excavations in Peru also produced the first complete sample of a giant penguin skull. “We really only had ideas about what the skulls of these animals looked like,” says North Carolina State University Assistant Professor Julia Clarke, one of the lead scientists who analyzed the remains. “[The skull] is quite different from any living penguin,” she explains. With an actual skull to examine, scientists can more accurately determine what some of the earliest penguins looked like. Although both of the new species had longer and more pointed beaks than today’s birds, the giant penguin had a super-sized beak that is longer than any beak found in any living or extinct penguin. The super-sized beak had a sharp, spear-like point at the end that scientists suggest was used as a weapon to catch fish. To support this massive beak, the penguin’s neck was thick and muscular.

The age of these new fossils pushes back the date of penguin migration from southern latitudes to low latitudes millions of years earlier than previous data had indicated. Scientists have long believed that penguins migrated to northern South America during a cold era, between four and eight million years ago, but these new fossils hail from a warm period more than 30 million years earlier. Penguin researchers were quite surprised to find penguins living in the tropics during a time period when the earth was even warmer than it is today. “We tend to think of penguins as being cold-adapted species, even the small penguins in equatorial regions today,” says Clarke, “but the new fossils date back to one of the warmest periods in the last 65 million years of Earth’s history. The evidence indicates that penguins reached low latitude regions more than 30 million years prior to our previous estimates.”

Clarke warns that although penguins might have started out living in warm climates, today’s penguins are cold adapted and sensitive to climate change. “These Peruvian species are early branches off the penguin family tree, that are comparatively distant cousins of living penguins,” she explains. “The data from these new fossil species cannot be used to argue that warming wouldn’t negatively impact living penguins.”

Published in Americas magazine by Chris Hardman