THE GIANT STONE HEADS on the island of Rapa Nui (Easter Island), Chile, have captured the imagination of countless explorers, dreamers and scientists. Hundreds of monoliths of solid volcanic rock provide indestructible evidence of man’s mastery over his environment. They hint at great feats of engineering and the ingenuity of men. Up close, the statues show their vulnerability. Their sharp features have eroded, growths invade their surface and many lie in piles of rubble.

A combination of natural and human forces threatens the statues, which are called moai in the native Rapa Nui language. To combat these forces and save the moai, teams of native and international scientists are working on reconstruction and restoration projects.

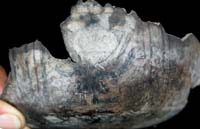

At 400 to 1000 years-old the moai are young compared to other archaeological monuments in the Americas, but the very properties of the stone that make them ideal for carving also make them susceptible to rapid deterioration. Nearly all of the statues were carved in the Rano Raraku Quarry located on the northeast corner of the island. Many of the statues never made it out of the quarry and remain there today in varying stages of completion. The red scoria stone used for headpieces found on some of the moai came from solidified froth of volcano lava.

These soft, volcanic rocks are particularly vulnerable to erosion from Easter Island’s relentless wind and rain. “When the stone is wet, the clays present in it absorb moisture and expand; as the stone dries, they contract. The internal stress of these repeated expansions and contractions results in microfissures within the stone which serve as channels for water migration and its corrosive effects,” wrote A. Elena Charola in a 1994 publication of the World Monuments Fund. Another natural process that weakens the stone is the growth of algae and lichens. Not only do they trap water—which plays a part in the wet/dry cycle of the stone—but they also eat away at the stone surface.

While nature has been hard on the moai, man has been even harder. The human toll on the statues has been immeasurable. Starting with the carvers themselves—who not only knocked over their beloved statues but also beheaded some of them—people have had a sort of fatal attraction to the heads. Archaeologists estimate that between 1,100-1,500 AD islanders meticulously carved approximately 900 statues and their accompanying stone platforms from the island’s soft volcanic rock. Most likely the carvers belonged to family groups who were competing with each other to produce larger and larger moai. The biggest statue, named el Gigante, weighs between 145-165 tons and would reach 71.93 feet high if it were standing. But for reasons unknown el Gigante was never raised and remains in the Rano Raraku Quarry.

The islander’s obsession with larger and more impressive moai wreaked havoc on the environment. More and more trees had to be cut down to provide scaffolding for the statues and to build wooden sleds to move the statues overland. By the time Dutch explorer Jacob Roggeveen landed on the island on Easter Day in 1722, he found a desolate landscape void of trees or bushes over 10 feet high with no birds, bats or lizards. The people were hungry and fighting amongst themselves. Sometime after contact with the outside world, the islanders knocked over and destroyed most of the moai probably as a result of clan warfare. Contact with the outside world brought new diseases, a new form of religion and kidnappings for the slave trade. By 1877 the native population of 15,000 had declined to a mere 111.

The relationship between man and moai is complex, and similar to the admirers of the past, modern-day man’s fascination with the statues has produced both positive and negative results. As the island’s only industry, tourism provides a way to make a living for the most remote civilization on Earth. Unfortunately the occasional unscrupulous visitor has encouraged islanders to sell broken parts of the statues for souvenirs. Further damage comes from foreigners and locals alike who defile the moai with graffiti or accidently step on fallen rocks or buried petroglyphs. In spite of admonishments from local tour guides, some visitors touch the statues or climb on their platforms. In the early 90s, the World Monuments Fund, reported an increase in graffiti by 20% in a two-year period.

At 400 to 1000 years-old the moai are young compared to other archaeological monuments in the Americas

Locals warn that the island is not prepared to support the number of tourists that come. According to Easter Island officials, in just 3 years tourism doubled from 22,000 visitors in 2003 to more than 50,000 in 2007. Not only does increased tourist traffic stress the monuments, masses of visitors strain the island’s resources as they struggle to deal with piles of trash and to meet the increased demand for food and water.

Although Easter Island has been an official historic monument and national park since 1935, it took until 1966 for the government of Chile to actually send a small staff to the island. The Rapa Nui National Park takes up nearly half of the island and includes nearly all of the moai sites. In 1995 UNESCO named Easter Island to its world heritage list of the world’s greatest monuments. The world is so captivated by the moai that Easter Island was a finalist in the New 7 Wonders of the World campaign in 1997 where 100 million people from around the world voted on the Internet for cultural heritage sites.

One of the first scientists to realize the archaeological and cultural significance of the site was University of Wyoming Professor William Mulloy, who tirelessly campaigned UNESCO for support to study the island’s monuments. During his first official mission to the island in 1966, Mulloy and Gonzalo Figueroa led a team of experts who developed a plan for studying, conserving and restoring Rapa Nui’s cultural treasures. What followed was a series of projects with international support that restored moai and their platforms and eventually the Orongo village from 1974-1976.

In 1986 Chile’s Centro Nacional de Conservación y Restauración worked with UNESCO to investigate possible treatment plants to prevent or slow deterioration of the statues. They chose a moai at Hanga Kio’e that had been re-erected but was highly deteriorated. After spending several months drying out under a protective tent, the moai was cleaned of all growths and dirt. The restoration experts applied a consolidation treatment to harden the stone and prevent erosion and a hydrophobization treatment to prevent water from seeping into the stone. Although these treatments have worked so far, they do not provide permanent protection of the moai and need to be reapplied periodically.

From 1992 to 1996 a team led by University of Chile archaeologists professor Claudio Cristino and professor Patricia Vargas completed an ambitious reconstruction project of ahu Tongariki, the largest and most impressive ceremonial center on Easter Island. Both Cristino and Vargas had extensive knowledge of the island’s monuments. From 1977 to 1996, they were part of the Easter Island Archaeological Survey, a University of Chile research program that recorded more than 20,000 archaeological sites and features. At its peak, the ahu Tongariki measured nearly 220 meters long, with a central platform measuring 100 meters and a wing on either side. A total of 15 statues weighing between 40 to 90 tons once stood on that platform.

The ahu Tongariki was leveled in 1960 by an earthquake that destroyed most of the central and southern regions of Chile. That deadly quake, some 3600 kilometers away, triggered a powerful tsunami that swept over the four meter high monument wall destroying the ahu platforms and dragging the statues inland. The broken moai were covered by tons of rocks from the destroyed platforms.

Fans of Easter Island feared that this great archaeological treasure was lost forever. Then in 1991 a Japanese company donated a crane to move the statues and partial funding for reconstruction costs. Cristino and Vargas led the reconstruction project which lasted 4 years and took a team of 50 people, most of them islanders themselves. Each rock fragment had to be studied, drawn and then input into the computer. Due to the soft nature of volcanic tuft, the rocks were in poor condition.

The team covered the moai with huge plastic tents and once they were dry, the statues could be moved without falling apart. “The first statue that went up was about 45 tons [and] went up in a few days,” Cristino explains. Painstakingly the team reconstructed the statues and placed them on their ahu platform. The result is a monument as tall as a five story building with 15 Moai and their topknots called pukaos.

A combination of natural and human forces threatens the statues

“We started from zero, little by little, trying to put this back together,” Cristino explains. “We used historic photographs and maps. Our main goal was the reconstruction of a largely destroyed monument.” For his mostly local staff, the project was a revelation. “Little by little [they] realized what their ancestors did was incredible. Their sense of pride was enormous.”

UCLA archaeologist Jo Anne Van Tilburg considers herself to be “a friend of the family” to the moai. Since 1982 she has surveyed the moai compiling what she calls “biographies” of 1045 sculptural objects that include full or partial moai. Van Tilburg runs the Easter Island Statue Project (EISP) with Co-director Cristián Arévalo Pakarati, a native Rapa Nui artist and surveyor. “The statues today do not look the same as when I saw them in 1982,” she says. “I could see the change over time.” Van Tilburg appealed to the Archaeological Institute of America to fund a preservation project to develop treatments for the fragile stone. With the grant, EISP installed a weather monitoring station near two moai in the Rano Raraku quarry. For the first time, scientists will be able to record fluctuations in wind, moisture and temperature near a statue and observe how the stone reacts to changes in weather. Van Tilburg says with this information, the team will be able to develop a treatment plan that could be used not only on the sample moai, but also on the 400 other statues that reside in the quarry.

As part of the same project, Research Associate Christian Fischer of UCLA and Conservador Jefa Monica Bahamondez P. of Chile’s Centro de Conservación y Restauración used a portable sprayer to apply two different types of water-repellent solutions to the test statues. Although the mixture will take several months to evaporate and dry, the team could see that it was already working when they poured water on the monuments and watched the water droplets run off the stone.

To better educate and manage visitors to Easter Island, the Corporación Nacional Forestal de Chile (CONAF)—the government agency that manages all of Chile’s national parks and reserves—opened a sustainable visitor center in May of 2011. The center is located at the entrance to the Orongo Ceremonial Village, which is one of the most visited archaeological sites on the island. “Easter Island is a landmark in the tourism world and that is why we need to work hard to preserve its resources as well as offer all kinds of information and education to its visitors, both national and international,” says CONAF Executive Director Eduardo Vial Ruiz-Tagle.

The moai of Easter Island tell different stories depending on the listener. For the islanders, they tell the story of their ancestors. For scientists they tell the story of a society gone awry and for the rest of the world they tell the story of human ingenuity. “Without something to remind us of the achievements or problems of the past, we don’t pay attention,” says Jo Anne Van Tilburg. To make sure that we continue to pay attention, scientists and conservationists are working to protect the statues for the generations of listeners in the years to come.

Published in Americas magazine, November-December 2011, by Chris Hardman

Although most of the khipu that remain today are from the Inca,William Conklin points out that the khipu are only part of a 2000-year history of Andean textiles. He has conducted detailed analysis of a group of Middle Horizon khipus from a time period 700 years before the Inca.

Although most of the khipu that remain today are from the Inca,William Conklin points out that the khipu are only part of a 2000-year history of Andean textiles. He has conducted detailed analysis of a group of Middle Horizon khipus from a time period 700 years before the Inca.